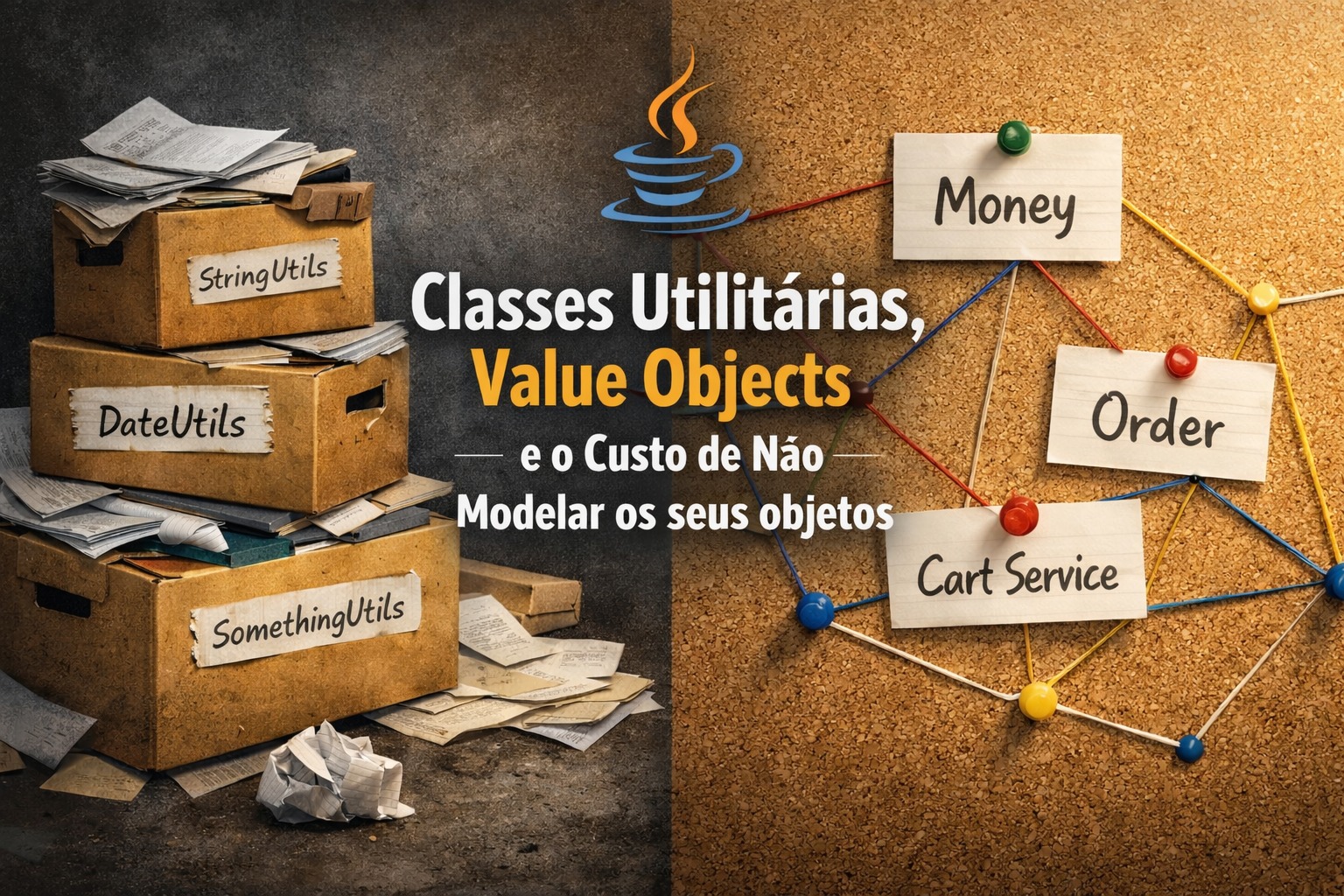

Utility Classes, Value Objects and the Cost of Not Modeling Your Objects

Understand why utility classes have become a recurring problem in Java projects and how Value Objects and DDD concepts can help better organize code and domain.

Sapiens IT Team

Written by engineers who build before they write.

In practically any project — especially in Java — it’s common to find utility classes that concentrate static methods responsible for executing things that the developer simply doesn’t know where to put. The result is almost always the same: a true salad of routines, often duplicated, carelessly dumped throughout the project, without clear criteria and without much thought behind it.

This has become an automatic reflex. Whenever a small operation arises, a SomethingUtils is created and we move forward, with the feeling that the problem has been solved. And technically, it has. The problem is that this recurring habit makes it increasingly less obvious where a particular business rule is — and worse, who it really belongs to.

Even in projects that claim to be object-oriented, we end up giving up the greatest potential of this paradigm. In the end, the code works, but it doesn’t communicate anything about the domain, much less about how it should be represented. It’s code that solves problems, but tells no story.

For a long time, I searched for a more pragmatic strategy that would help me decide when to use (or not) utility classes. It was from the combination of some concepts that I arrived at an approach that, at least for me, became intuitively easier to understand, apply and maintain. The first step is to understand the limits of a utility class: it should not be demonized — and that is definitely not the goal of this article. Joshua Bloch himself, in Effective Java, makes it clear that utility classes should only exist when there is no clear object-oriented concept for that behavior, in addition to warning about the constant risk of them becoming true repositories of methods without an owner.

A classic example of this appears in a simple domain, such as a cash register. Adding an add function in a money helper is a strong indication that something is out of place. Here, we’re talking about a behavior that clearly belongs to the domain: validation is an invariant of the object, and the operation speaks directly to the business language. Even so, it’s common to see something like this:

public class MoneyUtils {

public static Money add(Money a, Money b) {

if (!a.getCurrency().equals(b.getCurrency())) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Different currencies");

}

return new Money(a.getAmount().add(b.getAmount()), a.getCurrency());

}

}Another recurring case is when a static function ends up hiding a business rule that, in practice, should live in a domain service. Instead, it ends up in another Utils class, completely losing the context and original intention:

public class ShoppingCartUtils {

public static BigDecimal calculateFinalPrice(ShoppingCart cart, Customer customer) {

BigDecimal price = cart.getBasePrice();

if (customer.isPremium()) {

price = price.multiply(BigDecimal.valueOf(0.9));

}

if (cart.isCupomApply()) {

price = price.multiply(cart.cupom().discount());

}

return price;

}

}Although this reading helped a lot in my research, it still didn’t completely answer what I was looking for. The question remained: in cases where functions clearly belong to an object’s domain, how to organize this behavior? I arrived at some solutions that proved interesting.

First of all, it’s worth asking a simple question that is almost never asked: what, after all, is a Money?

In practice, many people answer this with a long, a double, or, being a bit more careful, a BigDecimal. And that’s it. The value continues traveling through the system, passing through DTOs, services, controllers and repositories, always accompanied by scattered validations and implicit rules that no one knows exactly where they live.

It’s precisely there that the Value Object concept begins to make a difference. Instead of treating money as a primitive type “a bit fancier”, we start treating it as a domain concept. A Money is not just a number: it has currency, rules, invariants and behavior. And as Vaughn Vernon reinforces in Implementing Domain-Driven Design, this type of concept is the perfect candidate for a Value Object.

When we model Money this way, it stops being a technical detail and becomes a central piece of the model. And more importantly: it is born valid. The rules don’t remain scattered in external validations or utility helpers — they are part of the object’s own definition:

public class Money {

private final BigDecimal amount;

private final Currency currency;

public Money(BigDecimal amount, Currency currency) {

if (amount == null || amount.signum() < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Amount must be positive");

}

if (currency == null) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Currency must be informed");

}

this.amount = amount;

this.currency = currency;

}

public Money add(Money other) {

if (!this.currency.equals(other.currency)) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Different currencies");

}

return new Money(this.amount.add(other.amount), this.currency);

}

}From this point on, the gain begins to spread throughout the system. This same Money can be reused in entities, services and even in DTOs, without needing to “break” the concept into primitive types all the time. An OrderDTO, an InvoiceDTO or a PaymentRequest now carry a Money, and no longer a loose BigDecimal accompanied by comments or implicit conventions.

This reduces duplication, eliminates repeated validations and creates a common language between application layers. The domain, DTOs and services start speaking the same language. And when a rule changes — for example, allowing negative values in a specific context — the impact is localized and explicit.

In the end, the problem is not in utility classes or static methods themselves, but in the automatic way they end up being used. Throughout the text, we saw that many of these cases arise simply because important domain concepts have not yet been modeled. Understanding basic ideas such as Value Objects, domain services and the natural limits of a utility class is already sufficient to avoid much of this accidental coupling and structural mess so common in Java projects.

When we start treating concepts like Money as what they really are — parts of the domain, with rules, invariants and behavior — the design begins to organize almost by itself. Validations start living where they make sense, rules stop being scattered in generic helpers and the code becomes more cohesive, more readable and easier to maintain. It’s not about following DDD strictly or applying complex patterns, but about knowing and applying some fundamental object-oriented concepts with intention. And, often, that’s already more than enough to get out of the infinite cycle of Utils.

If you want to deepen how to better organize your code, apply Value Objects and DDD concepts pragmatically, contact SapiensIT. We have the team and experience necessary to guide you with safety and clarity.

Written by the Sapiens IT team — engineers who build before they write.